Some people love discovering new bars or restaurants, others love finding vintage items at a thrift store, but me? I love gyms.

I recall visiting my sister when she lived in the deep suburbs of Chicago. There wasn’t much to do but go to her local Life Time Fitness. I delighted in its amenities as if it were a theme park resort. A full basketball court? AND a climbing wall? AND a pool with a sauna and hot tub? This is true paradise.

Gyms are not only playgrounds, but containers where people repeatedly and willingly experience physical discomfort in order to grow. Like a video game, as long as I'm willing to grind through the tasks, I gain experience points and can level up—in weight, reps, time endurance, VO2 max, etc. Input effort, output gains. As long as I can move my body, I know that I am alive, and if I challenge the limits of what my mind thinks my body can do, I can grow from it.

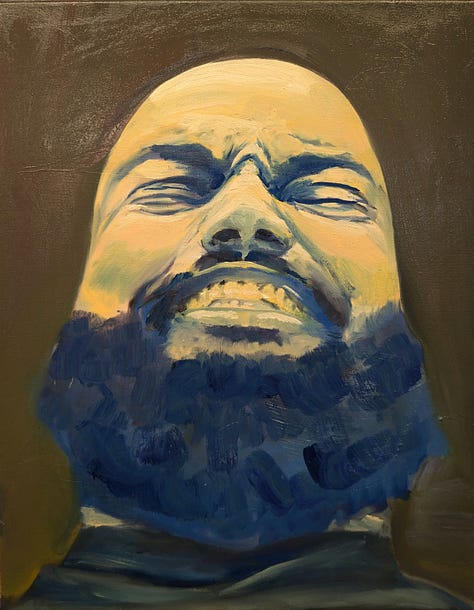

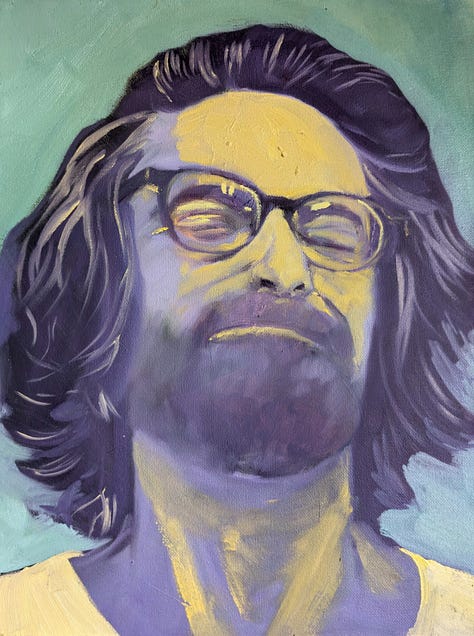

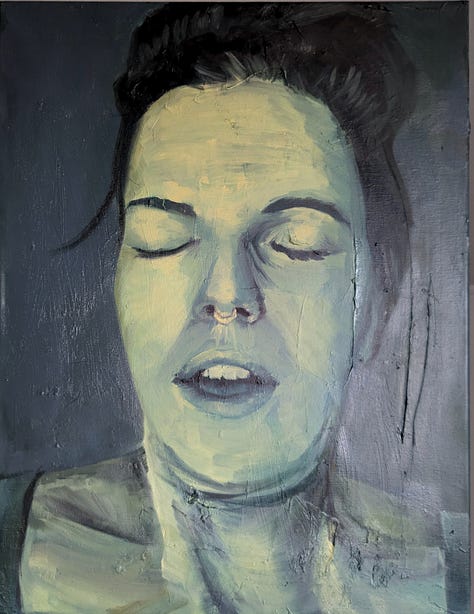

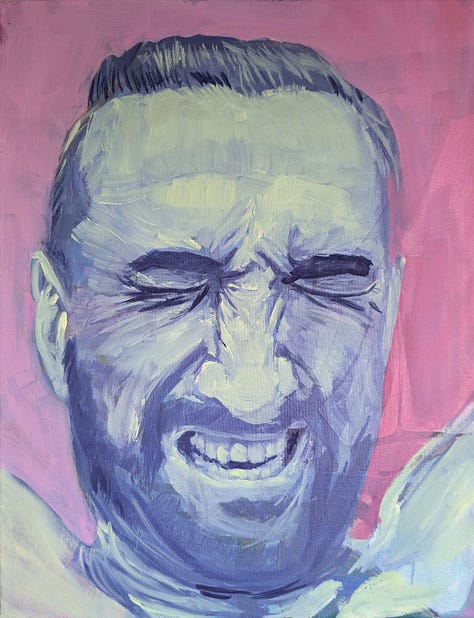

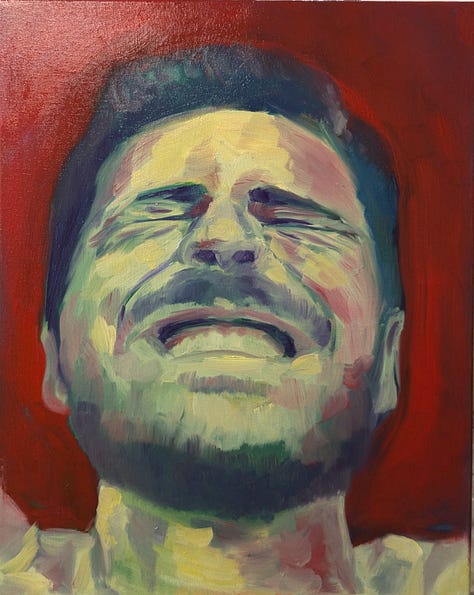

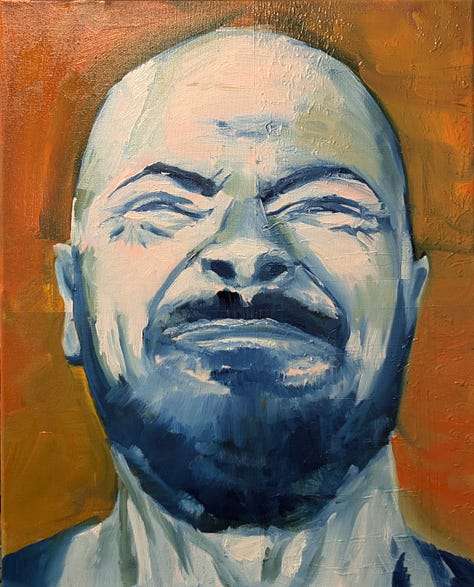

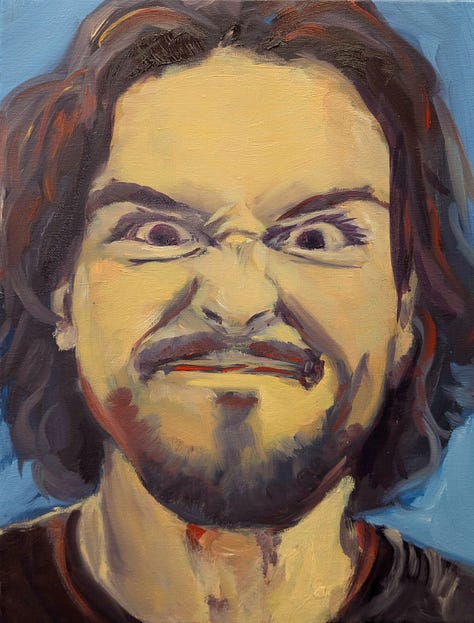

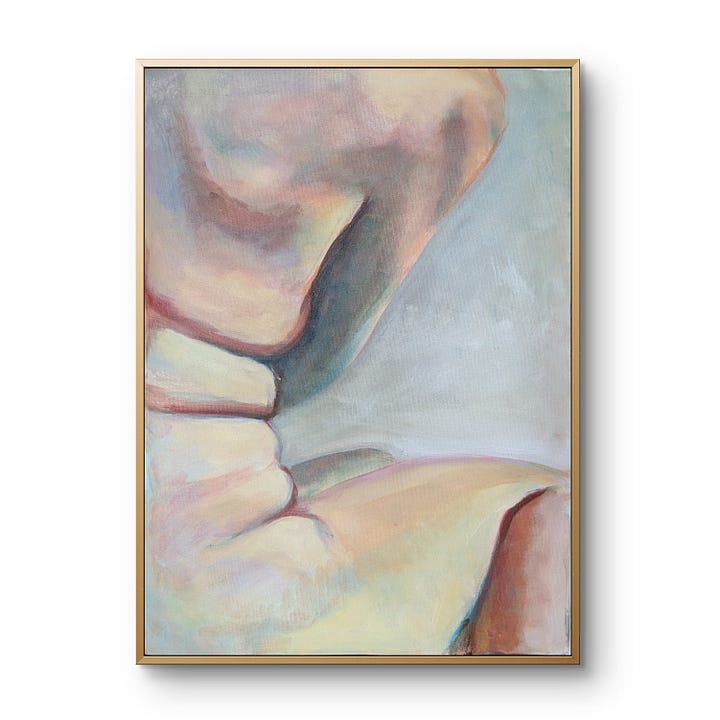

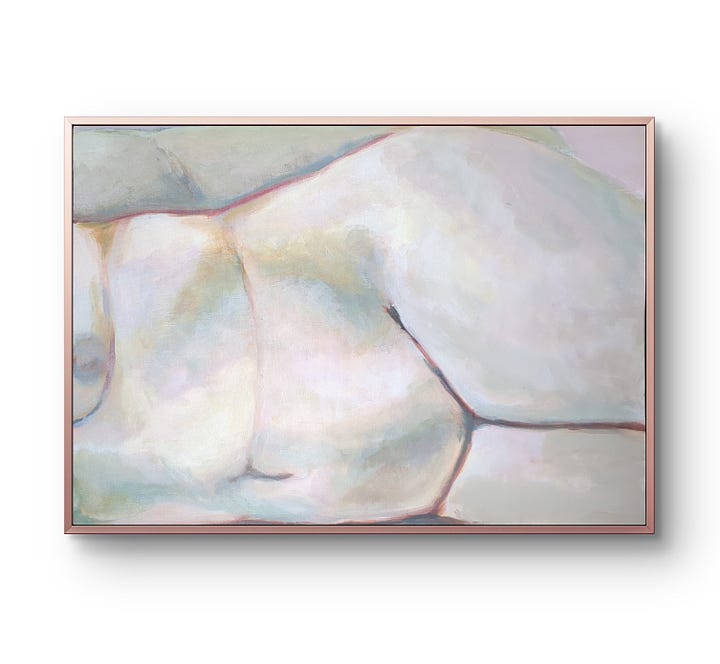

My “Face x Lift” series of paintings—of faces at the threshold of physical exertion—became a tribute to my love for fitness and my fondness of meeting and then surpassing one's limits. The human body has an amazing propensity toward adaptation.

In the gym, progress is beautifully quantifiable and visible. Compare that to wading through the unknown unknowns of pursuing art, where leveling up appears to be internal, subjective and self-defined. Milestones are arbitrary on this path and maybe even antithetical to my new persona. This tension between measurable progress and intangible growth would eventually lead me to question my approach to self-improvement.

My “Face x Lift” series captured people at their physical limits, celebrating the visible manifestation of effort. But what about the invisible work? The kind that requires letting go rather than holding on? This question brought me back to meditation.

Letting go

I grew up Buddhist, but didn't really take to meditating regularly until I attended my first 10-day Vipassana silent meditation retreat in 2017. It changed my life, and the experience made me conceptualize meditation as a practice in effortful focus. I would continue to meditate regularly, but stopped completely when I noticed that every time I went to sit, my mind would shoot off into space. When I would come back down to Earth at the chime of my 20-minute bell, I would realize I had not returned to my breath even once.

After a few years of not meditating, I attended a meditation at the Alembic in July last year. During the Q&A section, the meditation teacher advised “stop trying so hard,” when asked what he would tell his novice meditator self. “But of course, that is the advice to myself. Some people might need to try harder.”

Stop. trying. so. hard.

I realized I was striving so hard. Not just with meditation, but I was gripping so tensely to the idea that the way to achieve is to apply more effort. More SMART goals, better routines, ask for help, put in more time, more positive reinforcement, more negative reinforcement. The pressure to perform became the current I swam in.

With the guidance to “stop trying so hard,” I started to meditate in a looser and less effortful way. Paradoxically, it became much easier to come back to my breath.

Coming back to my body

In November I went to France along with Jenny to attend the Life Itself Autumn Praxis Residency. The open-ended residency centered around co-living in community and bills itself as a secular monastery where we meditate, cook, clean, and share vegetarian meals together.

I thought I wanted to approach the residency in my usual way and create a structured routine for my art practice. Instead, I found my body completely exhausted, unable to follow through on any such rigid ideals.

In the weeks leading up to my time in France, my boyfriend and I broke up and my subsequent weeks were filled with the distraction of visiting my friend at 8k altitude, becoming nocturnal for a 3-day art party, running last minute errands before my trip to France, and visiting my friend in New York before landing in Paris jet-lagged and sleep-deprived.

Without the constant stimulation of travel and socialization, I was finally still enough to feel my body again. I would find myself in bouts of intestinal discomfort, headaches, and lethargy. Rather than holding myself to the rigid rules the way I used to, I became intensely curious during my meditation about what my body was feeling. My body's signals were clear. Sleep, eat, pause, cry, explore, listen, scream.

In the meanwhile, my brain felt foggy and devoid of creativity. I felt unable to produce anything during that first week.

Non-symbolic experience

For the last year, bodily surrender had been a theme. What happens if I stop tensing? What if there's another way besides grinding to progress in life? While I was in the residency, I removed modes of imprisonment to time. I stopped using an alarm to wake me, I stopped religiously cultivating my calendar.

In my re-initiated meditation practice, I finally understood how to allow my human to do what it wants to do without the immediate reaction of shifting it to what I think it's “supposed” to do. The goal isn't to quiet the mind or tug myself into calm. The “goal” is to be exactly me, in the present moment, without judgement.

So I

listened

calmly,

openly,

and

with curiosity,

and

let

myself

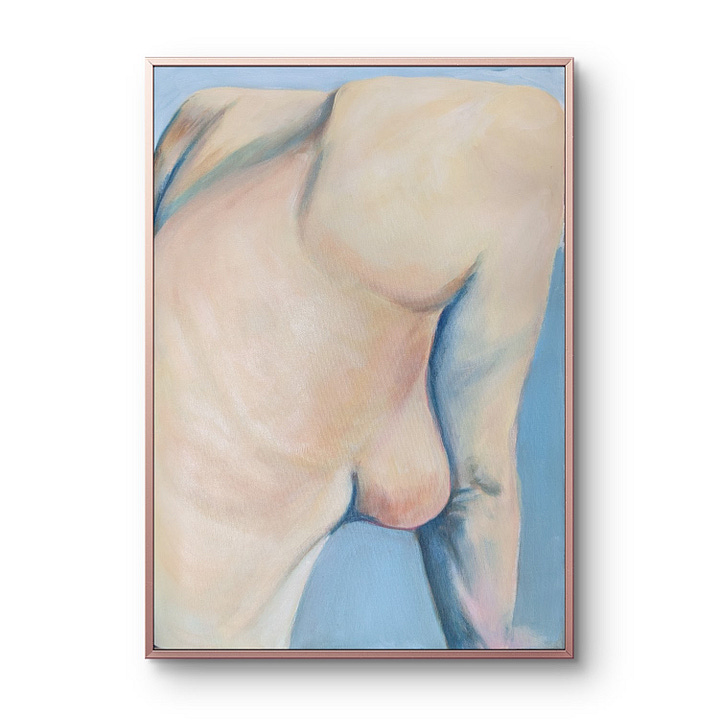

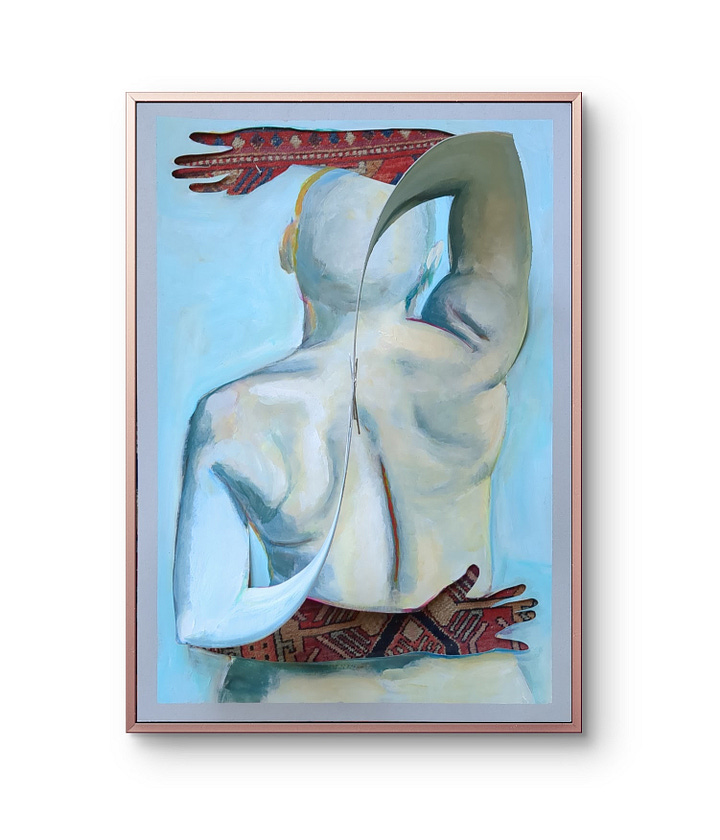

beIn the emotional, spiritual, physical and creative constipation of the first week, I let myself do whatever I felt like doing in order to let things pass. I went on long walks, I went to the swimming pool, I checked out the recyclery, I listened to podcasts about consciousness and meditation and art. I felt inspired by the works of Jenny Saville, and so the second week, I began painting at last.

Take my hand

At the heart of it, every act of creation is a kind of love-making. In making art, we reach for our beloved, and hope they take our hand.

— Jenny Lim

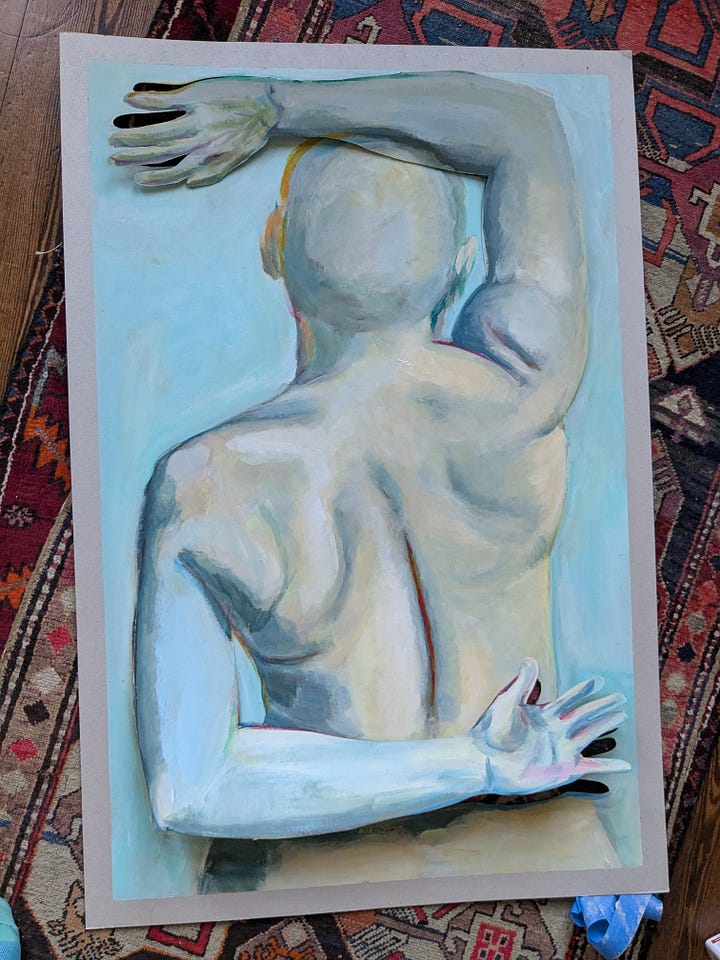

For the final week of the residency, I wanted to make a large piece that combined my two art disciplines: paper cutting and painting. I agonized over what image to make, still feeling a little creatively stuck. In the end, I wanted to create something that honored both my past and present selves—the one who found growth through disciplined effort, and the one who discovered power in surrender. It became a tribute to everything I love—fitness, bodies, and superpositions of the desire to be free and the desire to be held—and how these apparent contradictions have transformed me.

At once it feels trite to “do what you love” and then on second glance, romantic, simple, and effortlessly true. What would it look like to just love?

Perhaps it looks like this: holding space for both the gripping and the letting go, allowing each to teach us in their own time, and trusting that even our struggles to find balance are part of the practice.